From Chenab Bridge to Pir Panjal Tunnel: Why USBRL Redefines Mountain Rail Infrastructure

By Dr. Gagan Gera, Professor, Indraprastha College for Women, University of Delhi

Infrastructure in difficult terrain is defined by precision, and long-term impact. The Udhampur–Srinagar–Baramulla Rail Link (USBRL) exemplifies this ethos by expanding the frontiers of engineering and connectivity. Beyond enhancing regional access, USBRL stands as a reference point for delivering large-scale rail infrastructure in some of the world’s most challenging geographies.

For decades, Kashmir’s isolation was not simply a function of distance, but of uncertainty. Road connectivity through the Himalayas remained vulnerable to weather, terrain instability, and seasonal disruption, constraining mobility, trade, and economic integration. USBRL addresses this constraint at its root. By establishing a 272-kilometre all-weather rail corridor, the project has reduced physical distance, stabilised access, and embedded Kashmir within India’s national transport framework.

Executed in three phases, Udhampur–Katra, Katra–Banihal, and Banihal–Baramulla, the project demonstrates how incremental infrastructure delivery can generate immediate and lasting impact. The Udhampur–Katra section, operational since 2014, transformed access to Katra, the base for the Shri Mata Vaishno Devi Shrine, making year-round rail travel a reality and easing pressure on fragile road networks. This was not merely about convenience; it signalled a shift toward predictable, scalable mobility in the region.

The strategic significance of USBRL becomes most evident in the Katra–Banihal stretch. The Pir Panjal Tunnel, driven through unstable Himalayan geology, exemplifies how engineering innovation can overcome natural constraints without compromising safety. By cutting travel time from nearly six hours by road to around three hours by rail, the tunnel has delivered reliability in a region where unpredictability was once the norm. Such reliability is essential not only for passengers but for freight movement, supply chains, and economic planning.

Yet USBRL’s real success lies beyond engineering feats. Its stations have emerged as economic anchors. Reasi, Katra, Banihal, Qazigund, Sangaldan, and Budgam now function as nodes that link local economies to national markets. Agricultural producers, small traders, and tourism operators benefit from faster, more dependable access, reducing losses and improving price realisation. In South and Central Kashmir, rail connectivity has reshaped how goods move, how tourism scales, and how rural areas participate in broader economic systems.

Katra illustrates this transformation clearly. Designed as a modern, high-capacity station with multiple platforms, accessibility features, and solar energy integration, it has absorbed growing pilgrim volumes while generating employment and local enterprise. Similarly, Qazigund, the traditional gateway to the Kashmir Valley has enabled farmers to transport apples and other produce more efficiently, strengthening agricultural incomes and market linkages. Even remote stations such as Sangaldan demonstrate how infrastructure, when thoughtfully placed, can pull peripheral regions into the economic mainstream.

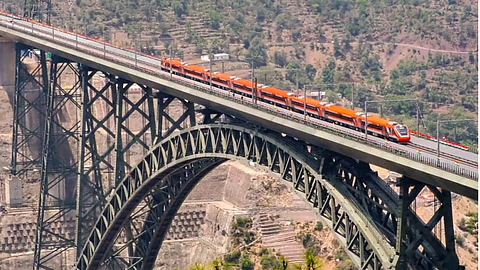

The completion of the Banihal–Baramulla section has fully integrated Kashmir into India’s rail network, but this achievement rests on sustained technical rigour. Rail India Technical and Economic Service (RITES), as a key consulting partner, contributed through technical audits of critical bridges including the Chenab and Anji Khad bridges—and the implementation of structural health monitoring systems. In a seismically sensitive and climatically volatile region, such measures are not optional; they are central to long-term resilience and public safety.

What USBRL ultimately offers is a model of infrastructure as an instrument of stability and inclusion. It demonstrates that connectivity projects in extreme terrain must be designed not only to overcome geography, but to deliver certainty of access, movement, and economic participation.

From the Chenab Bridge, rising above one of the deepest gorges in the world, to the Pir Panjal Tunnel threading through fragile mountain rock, USBRL reflects a shift in ambition. It shows that with sustained technical expertise, institutional coordination, and long-term vision, infrastructure can redraw the limits imposed by terrain. For mountain regions across the world grappling with similar constraints, USBRL is not just a completed project, it is a precedent.

Author:

Dr. Gagan Gera, Professor, Indraprastha College for Women, University of Delhi