Waiting time in port represents major inefficiency and GHG savings opportunity for international shipping

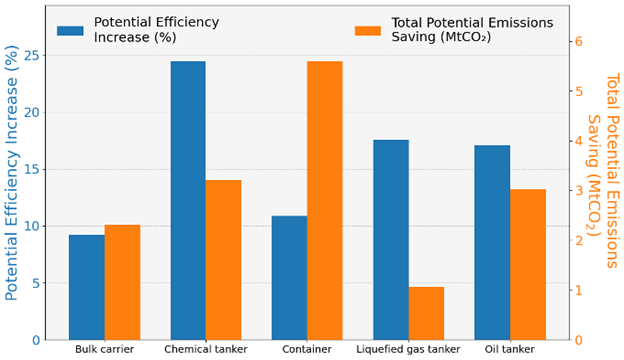

LONDON : A new study by UCL and UMAS, which analysed ship movements between 2018-2022, found that optimising port arrivals to take into account port congestion or waiting times could reduce voyage emissions by up to 25% for some vessel types. The average potential emissions saving for the voyages is approximately 10% for container ships and dry bulkers, 16% for gas carriers and oil tankers, and almost 25% for chemical tankers. The study finds that these ships spend between 4-6% of their operational time, around 15-22 days per year, waiting at anchor outside ports before being given a berth.

Dr Tristan Smith, Professor of Energy and Transport at the UCL Energy Institute, said: “The IMO set ambitious GHG reduction targets in 2023. Meeting those targets means unlocking all efficiency opportunities – including voyage optimisation and operations around ports. This will only happen if CII remains a holistic metric covering all emissions, and incentivising shipowners, charterers and port stakeholders to break down long-running market barriers and failures.”

Over the period 2018-2022, chemical tankers, gas tankers, and bulk carriers spent increasing waiting times at anchor before berthing, rising to 5.5-6% of time per annum, by 2022. Waiting times for oil tankers and container ships stayed approximately constant (around 4.5% and 5.5% respectively). Some of the increase in waiting times may be attributable to the port congestion caused during Covid-19 and by a post-pandemic surge in maritime trade.

The study also found that smaller vessels generally experience longer waiting times, though this varies by vessel type. Previous report by the authors, Transition Trends, has shown that poor operational efficiency is one of the main reasons for increased emissions in the period 2018 to 2022.

Dr Haydn Francis, Consultant at UMAS, said: “Our analysis highlights that the no value-add emissions associated with port waiting times are a current and growing issue across the shipping sector. This is just one piece of the broader operational inefficiency puzzle that can be targeted to generate the short-term emissions reductions that will need to be achieved before 2030. By targeting these idle periods, the IMO can help unlock significant emissions reductions while also driving broader improvements in voyage optimisation and overall operational efficiency”

The waiting behaviour stems from the common operational practices such as “first-come, first-served” scheduling and the “sail-fast-then-wait” approach—and is exacerbated by systemic issues such as port congestion, inadequate data standardization, inflexible charter parties (between ship owners and charterers), and limited coordination between the many wider stakeholders involved in a loading/unloading operation (port authorities, cargo owners etc.). The study shows that the CII regulation should consider all aspects of the voyage and not just the ‘sea-going passage’ as some have proposed, as it can incentivise stakeholders to come together to find solutions to reduce the GHG intensity of the ships across the value chain, instead of just isolating those parts where the shipowner or charterer are fully in control of. Limiting the CII to only parts of the voyage would mean that the well-known market barriers at the interface of ship-port operation would remain under incentivised and continue to persist, making the 20%-30% absolute GHG reduction in 2030, relative to 2008, specified in IMO’s Revised Strategy more difficult to achieve.

The work also highlights the contribution of port congestion to system-wide inefficiencies. Port congestion has been highlighted by low-income member states, as a disadvantage to them and their efforts to decarbonise. Although unable to be looked at in depth in this study, this suggests that there could be links between efforts to find system efficiencies at the interface between ships and ports, and the efforts to enable a just and equitable transition, which are an important feature of the design of mid-term measures.

Link to full report: https://www.shippingandoceans.com/post/waiting-time-in-port-represents-major-inefficiency-and-ghg-savings-opportunity-for-international-shi

About UCL Energy Institute

The UCL Energy Institute hosts a world leading research group which aims to accelerate the transition to an equitable and sustainable energy and trade system within the context of the ocean. The research group’s multi-disciplinary work on the shipping and ocean system leverages advanced data analytics, cutting-edge modelling, and rigorous research methods, providing crucial insights for decision-makers in both policy and industry. The group focuses on three core areas: analysing big data to understand drivers of historical emissions and wider environmental impacts, developing models and frameworks to explore energy and trade transition to a zero structures that enable the decarbonisation of the shipping sector. For more information visit www.shippingandoceans.com

About UMAS

UMAS is an independent commercial consultancy dedicated to catalysing the decarbonisation of the shipping industry. With our deep industry expertise, exceptional analytical capabilities and state-of-the-art proprietary models, we support our clients in navigating the complexities of this transition by providing groundbreaking data, analyses and insights. Internationally recognised for our work, UMAS delivers bespoke consultancy services for a wide range of clients including regulators, governments, NGOs and corporates. For more information visit www.umas.co.uk