Covid-19: The world economy is suddenly running low on everything

MUMBAI : A year ago, as the pandemic ravaged country after country and economies shuddered, consumers were the ones panic-buying. Today, on the rebound, it’s firms furiously trying to stock up.

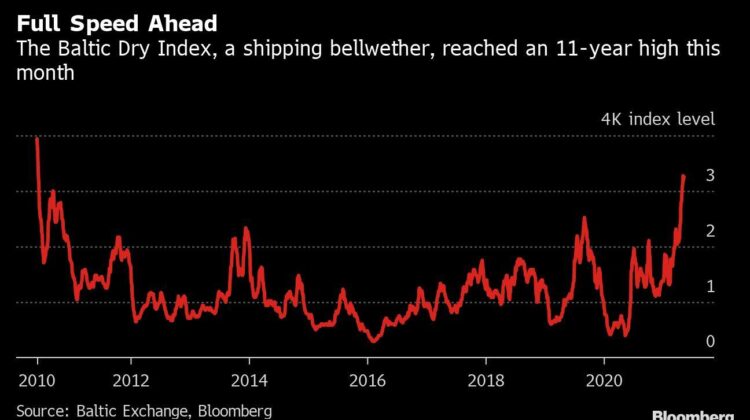

Mattress producers to car manufacturers to aluminum foil makers are buying more material than they need to survive the breakneck speed at which demand for goods is recovering and assuage that primal fear of running out. The frenzy is pushing supply chains to the brink of seizing up. Shortages, transportation bottlenecks and price spikes are nearing the highest levels in recent memory, raising concern that a supercharged global economy will stoke inflation.

Copper, iron ore and steel. Corn, coffee, wheat and soybeans. Lumber, semiconductors, plastic and cardboard for packaging. The world is seemingly low on all of it. “You name it, and we have a shortage on it,” Tom Linebarger, chairman and CEO of Cummins Inc, said on a call this month. Clients are “trying to get everything they can because they see high demand,” Jennifer Rumsey, the Columbus, Indiana-based company’s president, said.

“They think it’s going to extend into next year.” The difference between the big crunch of 2021 and past supply disruptions is the sheer magnitude of it, and the fact that there is — as far as anyone can tell — no clear end in sight. Big or small, few businesses are spared. Europe’s largest fleet of trucks, Girteka Logistics, says there’s been a struggle to find enough capacity. Monster Beverage Corp of Corona, California, is dealing with an aluminum can scarcity.

Further exacerbating the situation is an unusually long and growing list of calamities that have rocked commodities in recent months. A freak accident in the Suez Canal backed up global shipping in March. Drought has wreaked havoc upon agricultural crops. A deep freeze and mass blackout wiped out energy and petrochemicals operations across the central US in February. Less than two weeks ago, hackers brought down the largest fuel pipeline in the US, driving gasoline prices above $3 a gallon for the first time since 2014.

For anyone who thinks it’s all going to end in a few months, consider the somewhat obscure US economic indicator known as the Logistics Managers’ Index. The gauge is built on a monthly survey of corporate supply chiefs that asks where they see inventory, transportation and warehouse expenses — the three key components of managing supply chains — now and in 12 months. The current index is at its second-highest level in records dating back to 2016, and the future gauge shows little respite a year from now. The index has proven unnervingly accurate in the past, matching up with actual costs about 90 per cent of the time.

A growing chorus of observers are warning that inflation is bound to quicken. The threat has been enough to send tremors through world capitals, central banks, factories and supermarkets. The US Federal Reserve is facing new questions about when it will hike rates to stave off inflation — and the perceived political risk already threatens to upset President Joe Biden’s spending plans.

Even multinational companies with digital supply-management systems and teams of people monitoring them are just trying to cope. Whirlpool Corp CEO Marc Bitzer told Bloomberg Television this month its supply chain is “pretty much upside down” and the appliance maker is phasing in price increases. Usually Whirlpool and other large manufacturers produce goods based on incoming orders and forecasts for those sales. Now it’s producing based on what parts are available.

The strains stretch all the way back to global output of raw materials and may persist because the capacity to produce more of what’s scarce — with either additional capital or labour — is slow and expensive to ramp up. The price of lumber, copper, iron ore and steel have all surged in recent months as supplies constrict in the face of stronger demand from the US and China, the world’s two largest economies. Crude oil is also on the rise, as are the prices of industrial materials from plastics to rubber and chemicals. Some of the increases are already making their ways to the store shelf.

Food costs are climbing, too. The world’s most consumed edible oil, processed from the fruit of oil palm trees, has jumped by more than 135 per cent in the past year to a record. Soybeans topped $16 a bushel for the first time since 2012. Corn futures hit an eight-year high while wheat futures rose to the highest since 2013. A UN gauge of world food costs climbed for an 11th month in April, extending its gain to the highest in seven years.

Source : Business Standard