Ever Given’s Suez Canal blockage still disrupting global shipping

TOKYO/CAIRO : Global shipping is still suffering ramifications a month after the giant Ever Given container ship ran aground in Egypt’s Suez Canal and blocked the key waterway for about a week.

Ports across the world are still clearing cargo logjams from March 23 when the ship first got stuck in the main shipping route between East and West. But even before the accident, global shipping was already facing disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

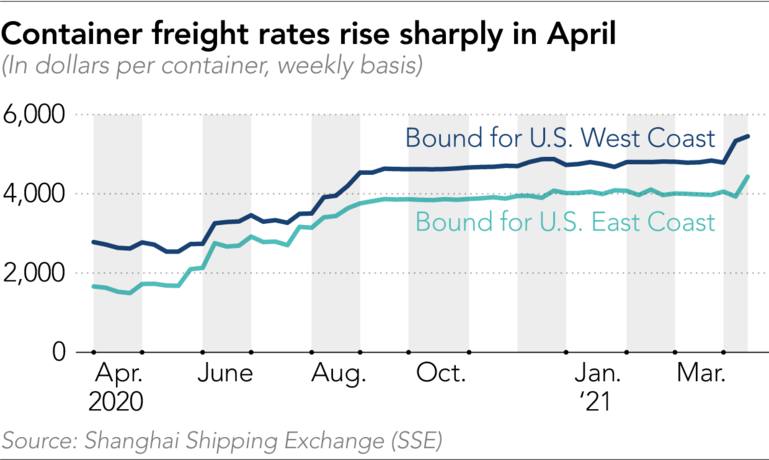

Since Ever Given’s problems in the Suez Canal late March, container freight rates have surged more than 10% to a new high. This has forced companies to resort to airfreight which is substantially more expensive and rail transportation which is considerably slower. As such, global supply chains are still snarled up.

Spot freight rates for containers bound for the U.S. West Coast from Shanghai have increased to $4,432 per 40-foot container, according to China’s Shanghai Shipping Exchange, or SSE. Those for containers bound for the U.S. East Coast have climbed to $5,452 per 40-foot container. The figures are the highest since survey began in 2009.

Freight rates for containers bound for Europe are $4,187 per 20-foot container, also up more than 10% from the end of March. About 100 ships are still waiting to enter the Port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands, Europe’s largest sea port.

There is no end to the congestion in sight yet. Charlotte Cook, head trade analyst at VesselsValue, a British ship data provider, said that the port would remain congested through May as like others elsewhere, it has to cope with scheduled vessels as well as those held up by the blockage.

The situation is exacerbated by a resumption in some manufacturing operations, which had been mired in the doldrums due to the coronavirus pandemic. This trade resumption had pushed the volume of container traffic from Asia to the U.S. to a record high in March.

Furthermore, the blockage of Ever Given, which is owned by Shoei Kisen, part of Japan’s Imabari Shipbuilding Group, came at a time when cargo processing at U.S. ports was already struggling to keep pace with soaring cargo volumes due to a labor shortage, which was also in part a consequence of the pandemic. Ships that were stuck due to the blockage then turned around to head to American ports, worsening the congestion there.

A.P. Moller-Maersk, the world’s largest container shipping company based in Denmark, suspended new spot cargo bookings on March 31 to avoid confusion and until now, has yet to expand bookings to pre-accident capacity.

This has meant holdups all along supply chains. An official at a Japanese precision equipment manufacturer said, “Although printer sales are humming along in the U.S. due to stay-at-home consumption, (our company’s) local inventories are becoming scarce because of arrival delays.”

Some shipping companies are now investing heavily in vessels amid the spike in freight rates. According to British research firm Clarkson, the number of new orders for container ships between January and March this year stood at 138, already exceeding the 105 ships ordered in the whole of 2020.

Yet, those orders take two to three years to fulfill, which does not solve the problem of tight supply now and could in fact weigh on company operations in the future. The 2016 bankruptcy of Hanjin Shipping, a major South Korean shipping company, is a case in point. The company boosted orders for new vessels during good times but struggled with the subsequent slump in demand.

Some of the demand that has shifted to rail and airfreight may also not return. The Suez blockage highlighted the risks posed by overdependence on a particular transportation route.

Toyo Trans, a Tokyo-based subsidiary of Toyo Wharf & Warehouse, launched a new service from Japan to Europe in January on Russia’s 9,300-km Trans-Siberian Railway. So far, that service has been used to transport machinery parts and chemical products two to three times a month from Japan to Europe.

“Unless the coronavirus outbreak is brought completely under control, normalization (of global shipping) is difficult,” said Takuma Matsuda, a professor at Japan’s Takushoku University.

Cargo owners are also looking to air freight. According to the Tokyo-based Japan Aircargo Forwarders Association, or JAFA, the volume of Japanese exports by air on a consolidated cargo basis in March skyrocketed 63% from a year earlier, reaching the highest level in 29 months.

The number of chartered cargo flights operated by Nippon Express, Japan’s largest international forwarder, between January and March this year saw a 2.5-fold increase to 261 from the preceding October-December period.

Among the key items being sent by airfreight, which costs over 10 more than by sea, are auto parts and semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

Tokyo-based Foster Electric, which makes speakers for vehicles, is exporting some of its products by air rather than sea, but the increase in transportation costs has led the company to forecast a fall of up to 900 million yen (about $8.35 million) in its operating profit for the year ended in March.

Wolfgang Lehmacher, a former head of supply chain and transport industries at the World Economic Forum, pointed out that despite higher costs, different routes and alternative methods would strengthen global supply chains.

Source : Nikkei Asia